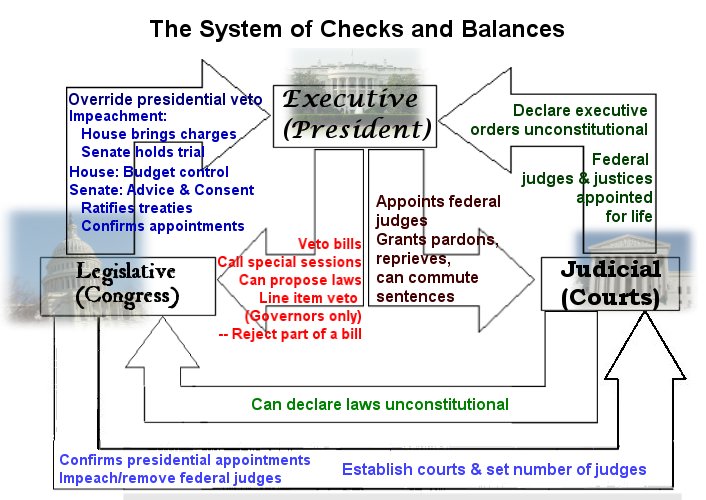

At this point, a summation of previous points might be in order. As I see it, there are at least three major flaws in the traditional concept of federalism. First, far from uniting the American colonists into a nation-state, the war for independence created thirteen separate and competing identities incompatible with national governance [1]. Second, the fact that federal institutions were modeled on the British system ensured that mechanisms of checks and balances would fail to operate, allowing the central government to decide for itself what it could and could not do [2]. Third, the use of complexity as a substitute for distinct social classes has actually distorted public perceptions of institutional responsibility. This particular problem will be the focus of today’s topic.

With the central authority in these States United balanced between two amorphous national parties, the complexity and overlapping jurisdictions of the federal system disguises the true source of particular decisions. As Machiavelli points out, “[g]enerally, [people] judge by the eye rather than the hand, for all […] can see a thing, but few come close enough to touch it” [3]. There is a regrettable truth in these words. Very few people have the time, money or patience to grapple with the nuances of policy-making at the federal level. As a consequence, the average American citizen must rely on political slogans, sound-bites, and party talking points for information on the behavior of central institutions. This provides a highly malleable atmosphere in which unpopular decisions or abuses of power can be imputed to one branch or another, burying culpability beneath an avalanche of parliamentary rules or arguments over executive privilege and national security. Federal legal codes alone are so complex that even trained experts in the field have trouble explaining it to the public in a digestible form.

In such a context, only professional bureaucrats, government lawyers, and political power brokers have access to enough specialized information to develop and implement policy. To be sure, the “people” can vote, but so long as they remain in the dark as to what they are voting for, the national government need not fear the ire of the governed. In this way, only those select few which posses the financial means to facilitate a permanent representation of their interests in Washington D.C. (via lobbyists and party donations) can have a meaningful impact on domestic and foreign affairs. And all of the consequences of such influence are funded at the “people’s” expense—that is, the taxes and lives of the vast majority of citizens who have little say in the matter and even less to gain. Bank bailouts, dubious foreign wars, government intervention in the economy, and unsustainable military and welfare establishments, are only possible in an environment where the seat of power is too far removed for its citizens to understand it, let alone control it.

Of course, none of this is unique to the United States. It is, however, quite particular to a specific form of government: empire. Yet, all is not lost. Having recently become acquainted with the consequences of imperialism, the present generation possesses both the incentive and the opportunity to actively reverse this trend. American federalism has within it all the necessary mechanisms and institutions to shift power away from the central government, without having to resort to violence. The focus of the coming decades must be on formulating a practical division of labor between central and local institutions. If the United States are to be reborn, we must re-examine the contemporary approach to American Union; there must be a “new” federalism for a new century.

Thursday, June 11, 2009

The Federalist Dilemma part 3: the price of complexity

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment